Phil at his drawing desk

By Belle Butler

Sitting in half shade, half sun on the veranda of his Lawson home, Phil Somerville tells me that juxtaposition is an effective tool for cartoonists: “Putting two unlikely things together can spawn an almost original idea”. The happy outcome of placing two opposing or apparently unrelated things together can be that something fresh is illuminated. Layers of thought-provoking insight from the in-between are exposed. This explains why so many good cartoons successfully walk an improbable line between absurdity and truth.

Phil himself is in some ways a juxtaposition, the result of two contrasting origins. His mother was a devout Catholic, his father an agnostic jazz musician. On the surface, an unlikely pairing: Catholicism and jazz. One rigid, the other free flowing; one prescribed, the other improvised. But as Phil emphasises throughout our conversation, humans are messy, things are not black and white.

Somewhere in their in-between, his parents had musical talent in common. Both were pianists. And his father had something else. In line with his jazz inclinations, he had the ability to bend. He was in love, so he accepted the Catholicism and allowed his kids to be baptised. He worked tirelessly as a freelance musician in order to pay for his children’s Catholic education.

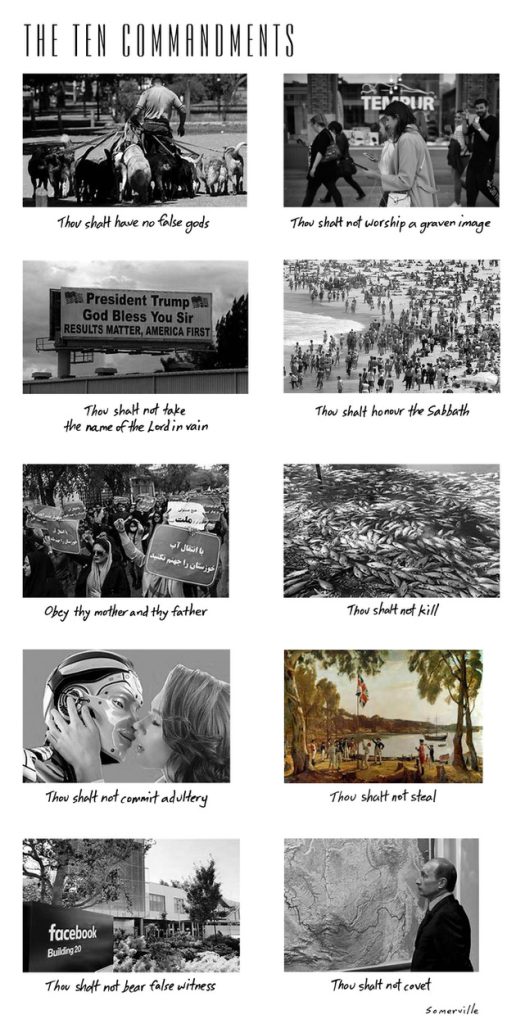

One of Phil’s cartoons using photographic images ‘Ten Commandments’

Phil spent first and second class at Holy Cross in Woollahra, then went to Waverley College for the remainder of his schooling. At both, he experienced unfathomable violence. “It was brutal,” he says. “The brutality was mostly from the Brothers, but the lay teachers were told they had to do the strapping and beating regularly. I mean, it was never for good reasons. It was just, they believed there had to be a dose of it and discipline every day. A bit like spinach, you know, it was good for the health in the long run. There was also a requisite amount of sexual abuse going on. Fortunately, this was part of my religious education I managed to skirt.”

Phil recalls crying a lot and other students shying away from him because of it. “I just never developed any armour for it,” he says. “Other guys, they knew how to survive this. They were stronger. They knew the game. For me, it was always in terms of abuse of power and injustice.”

It was amongst these hard edges of punishment and the blacks and whites of Catholic education that Phil discovered his unique access-key to survival. Humour. The school bully used to hit him with a lead pipe he kept down his trousers, but one day, Phil worked out how to make him laugh. “I told a joke and did some magic tricks. I was about 14. And he stopped hitting me. So, logic took over and I thought: Oh, there’s a connection here! And it started from that.”

What followed was a successful career in class clownery that grew (through the usual circuitous route life takes) into a successful career as a cartoonist. Phil drew caricatures of his teachers and sold them in the playground. He honed his delivery by closely examining the mechanics of the jokes he consumed while watching what he calls the golden age of TV, an era when television executives “placed premium trust in the writers and directors”, took more risks and interfered less. He read what he could of Punch and the New Yorker. “That’s when the lightbulb went on,” he says of realising these outward-thinking American cartoonists were actually getting paid for what they did. “I thought: It doesn’t just have to be a hobby. It doesn’t just have to be a secret vice, drawing cartoons, it could actually earn me a living. Maybe even some esteem.”

Tools of the trade

It might have been a common realisation among Phil’s peers. He acknowledges the profession is one that attracts cast offs and introverts, those who were bullied at school, people who learnt the value of making others laugh. “Later, if they wanted to translate it into earning a living, they realised there’s a lot more seriousness to this than they first understood,” he says. “That there might be a more serious purpose and goal for it. And there is.”

It’s a question I was eager to ask: what does a cartoonist see as the ideal aim of the cartoon? By now I understood that Phil rarely has a single answer for a single question. There is never just one way to look at it. “For some cartoons the goal is to change society. And that’s rarefied. That’s a rarefied wish, aspiration,” he says. “Most of us want two things. The self-indulgence that is within the art of it, that the cogs and spindles of this delicate little cartoon world we’ve created turn sweetly. And perhaps that we’ve done something a bit better than we did yesterday, that we’ve learned something. That’s the internal pride of the artist, or craftsperson. Then getting out of the self-indulgent, the altruistic reason is to reach people you’ve never met, and you never will meet, and add something positive to their day.”

It’s an interesting point. One of the first things Phil had said to me was that his profession was a negative one, that cartooning was a ‘negative artform’. An editor he had worked with had accused cartoonists of really ‘pulling things down’. And yet one of the ideals in a cartoonist’s mind is that their work would add something positive to a viewer’s day. It’s yet another juxtaposition: by presenting something negative, you can bring about a positive outcome. The delivery of it via humour seems to be the key. “We’re trying to actually introduce ideas and get people to think. To even think about unpalatable things. So, it’s negative on the surface but what happens underneath… humour adds the positive.”

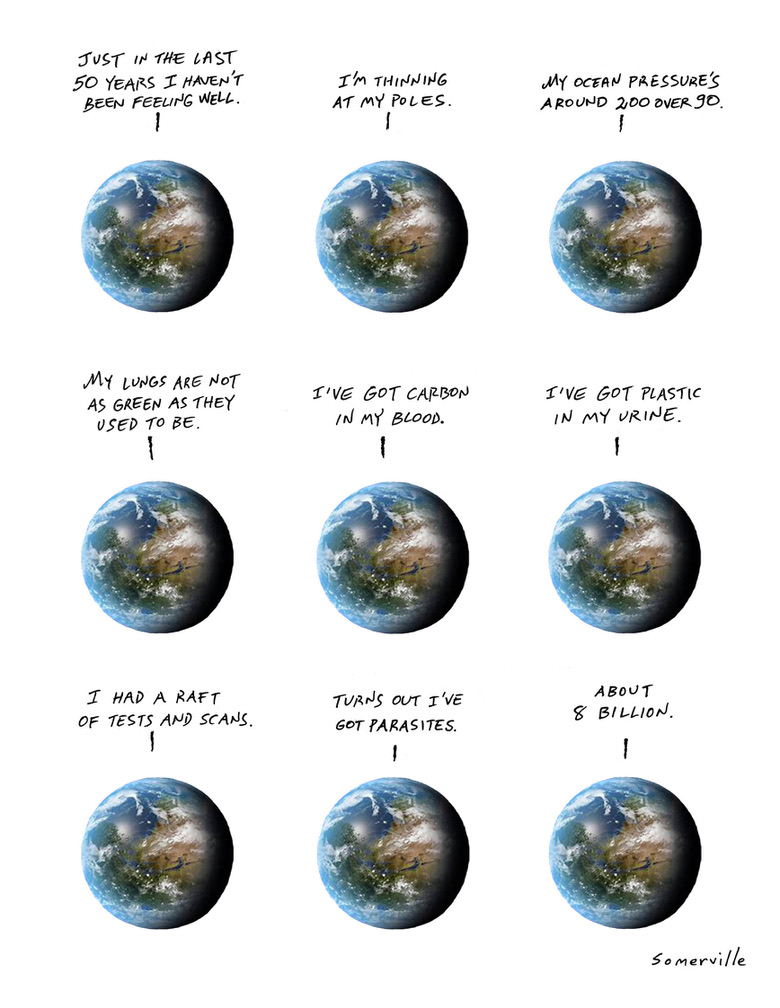

Earth Health Chat

Phil attributes positive reactions to the release of tension that viewers experience via laughter as being a result of some enlightenment on a topic that might have troubled them. “People will have a good reaction because they haven’t seen something through a certain prism,” he says. “Then a drawing has given them a bit of light on the topic, and it made them feel less overwhelmed by this issue.”

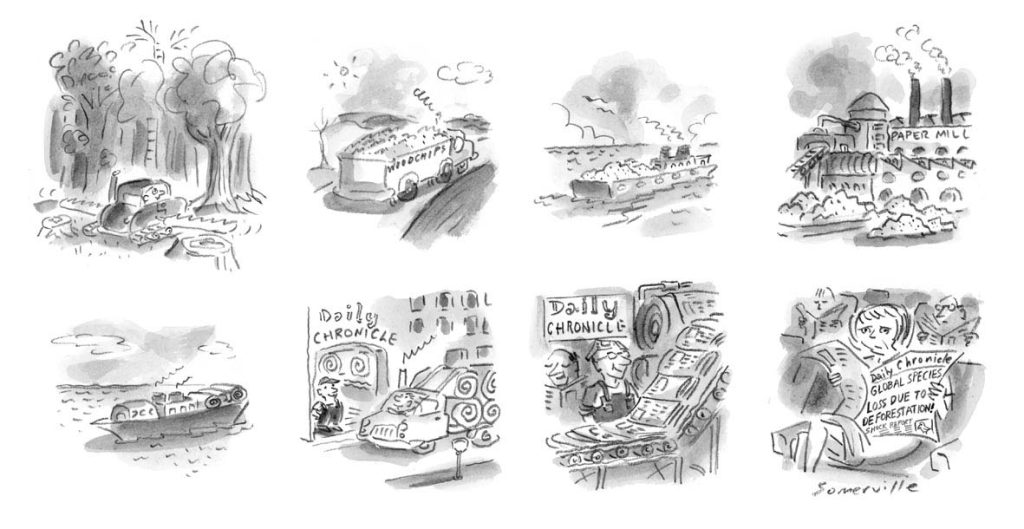

In this way, Phil sees the value of cartoons in dealing with pressing and overwhelming matters of environmental issues, including climate change. Some of his cartoons have appeared in the Australian Conservation Foundation magazine ‘Habitat,’ and a cartoon from his private subscription was adopted by two branches of the Extinction Rebellion movement. The cartoons still emerge from the negative, but by elucidating the error of going down certain paths, the cartoonist might help to change societal opinion and perhaps even incite action.

‘Paper Industry’ – originally published in the Australian Conservation Foundation magazine, Habitat.

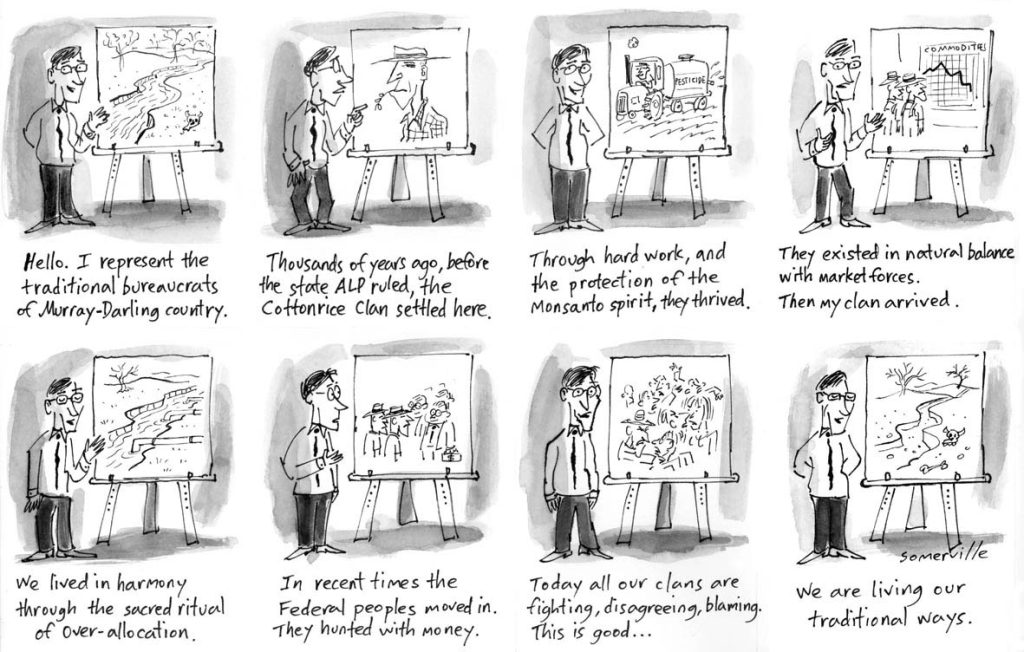

‘Murray Darling River’ – originally published in the Australian Conservation Foundation magazine, Habitat.

Perhaps provoking discomfort is an essential step in leading to action. If you are sitting uncomfortably, you move your position. If you don’t notice you are sitting uncomfortably, why move? A good cartoon might be a pain-like mechanism to the brain signalling that it’s time to move.

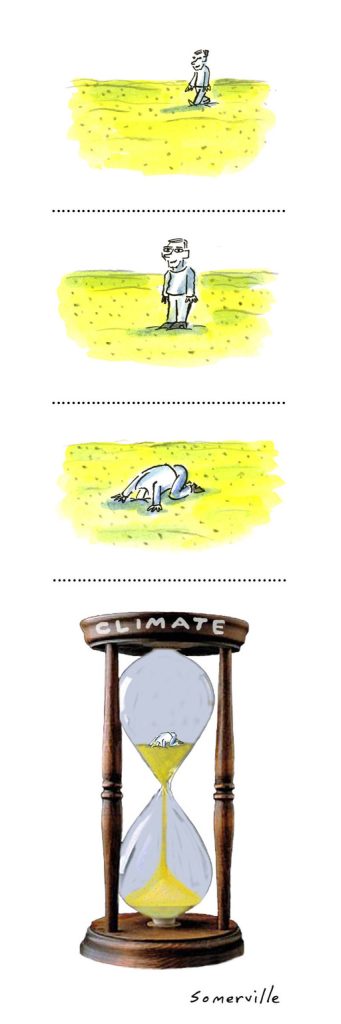

Considering the acceleration of climate change and related problems, Phil emphasises the constraint of what he calls ‘one of the most endangered resources’: time. “The qualifier for me,” he says, “is whether we can get this enlightenment to happen in the public that we think we are part of changing, whether we can we get it to happen in time.” Although he bemoans the devaluing of his craft due to digital proliferation of freely accessible cartoons, he also cites the positive side-effect of it, which is that the public is being exposed to a broader variety of ideas, which might (hopefully) result in a faster rate of change.

‘Hourglass’ – Phil’s cartoon was adopted by the Extinction Rebellion movement.

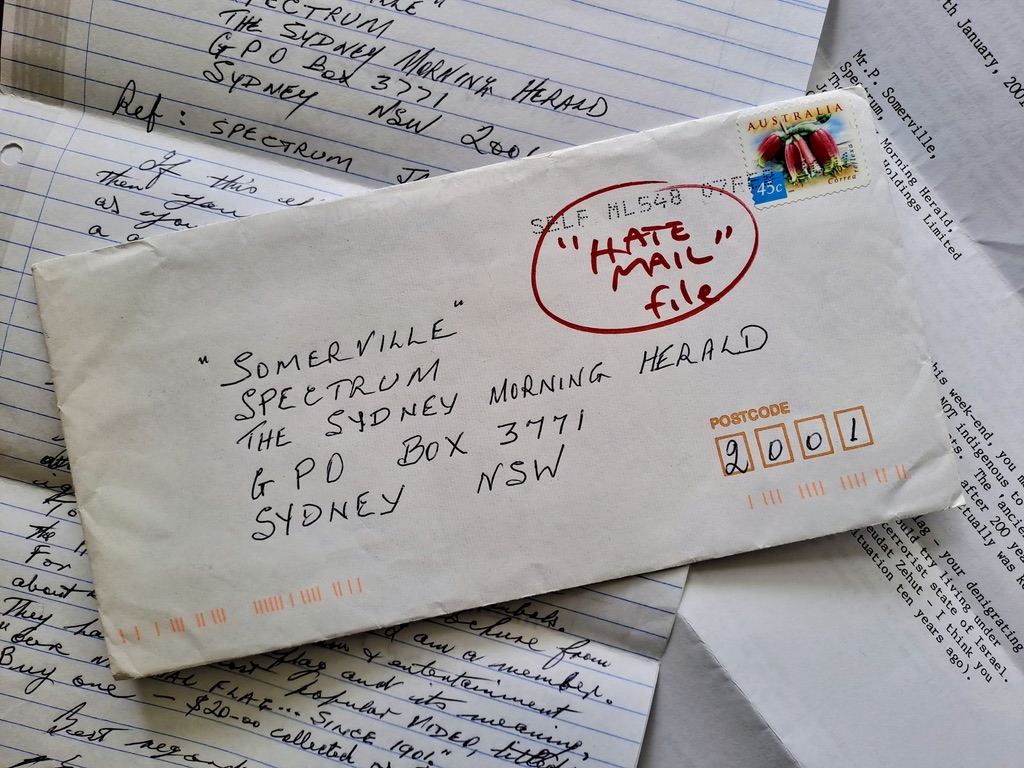

In dealing with wicked problems, it’s impossible to skate through without encountering tangles. Phil has been no exception, attracting a decent collection of hate mail while contributing to the Sydney Morning Herald in the 1990s, as well as one death threat (although he didn’t take this too seriously on account of the bad spelling). While a cartoon may play with the mash up of two unlikely things, the result is the likely provocation of two opposing responses, positive and negative.

“When people have had bad reactions, it was the topic, or the way I tended to it,” says Phil. “It was seen as either tasteless, racist, sexist, ageist, all of those ‘ists’.” He adds that there have been instances when cartoons had acted as a trigger for something very personal, or when they have been received as an attack on something a viewer held as untouchable – God for example.

‘Hate mail’ is a part of the cartoonist’s life.

While it has never been his intention to aimlessly trigger feelings of anger or personal offence, Phil has made it his practice not to disregard these reactions to his cartoons. It seems an integral part of his practice to openly receive them. While viewing as ‘strange logic’ anyone writing a complaint, he stresses the importance of attempting to understand where they are coming from. Doing so spawns his own deeper understanding of things. “I don’t like it when I hear cartoonists saying they’re just a bunch of loonies. That’s hypocritical, because we’re trying to get them to think deeper about things, then why should we be superficial?”

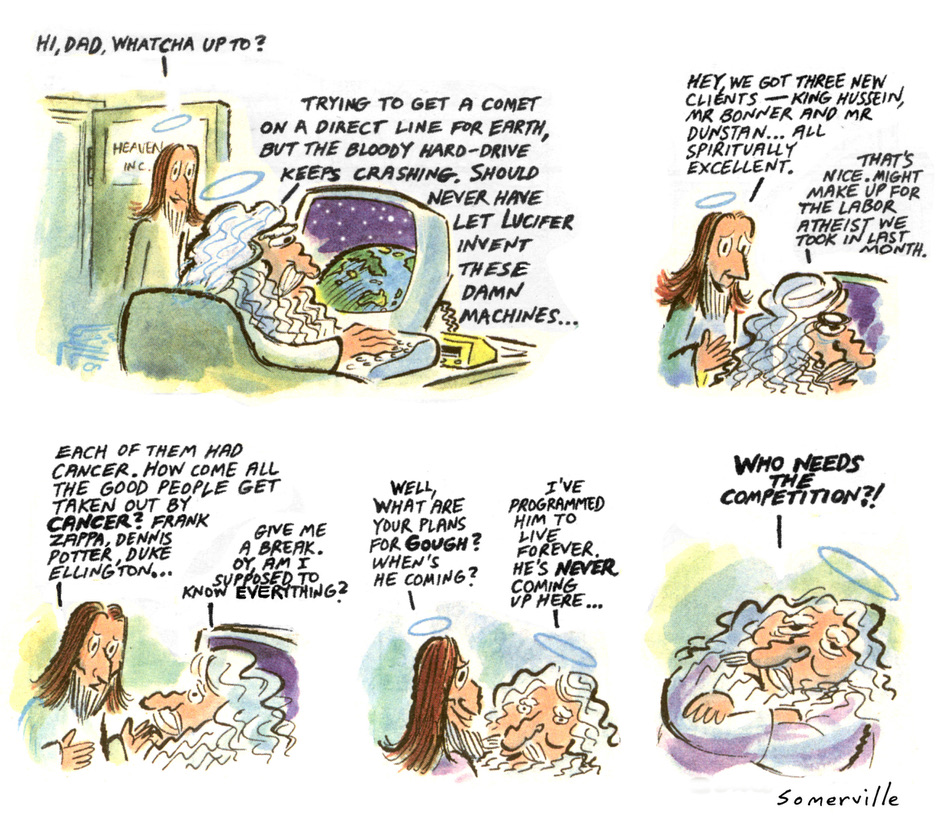

When I ask Phil about his career highlights it’s fitting that he chooses two that were on opposing ends of the response spectrum. It’s as if he requires one from each extreme to keep him balanced. The first was meeting Gough Whitlam in his office and having a deep and meaningful “yak” that lasted two hours. From death to the limitations of governance, they ticked off the hairy subjects.

This was the happy outcome of a cartoon Phil had produced for the Sydney Morning Herald in celebration of ex SA Premier Don Dunstan after his death. Whitlam loved the cartoon and asked to purchase it. Phil said he could have it for free, but the caveat was that he had to give it to him in person.

‘Stay-In-Touch’ – the cartoon that resulted in Phil’s career highlight of meeting Gough Whitlam.

After waiting for a while outside Whitlam’s office, Phil heard a booming voice: “Where is this retrograde sample of humanity?” Then Whitlam hobbled out on a crutch and with bandages on his foot.

Phil looked at the foot and said: “What’s going on?” Whitlam replied: “Oh it’s minor surgery comrade, I had something painful and ugly removed from my foot.” So, Phil said: “Was it Wilson Tuckey?” Whitlam immediately laughed and said, “Come into my office, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” Phil left with a career highlight as well as a deeper appreciation for his own artform. “You’re the replacement for the ancient philosophers,” said Whitlam. Phil’s response was: “Well, we’re on about the same income level.”

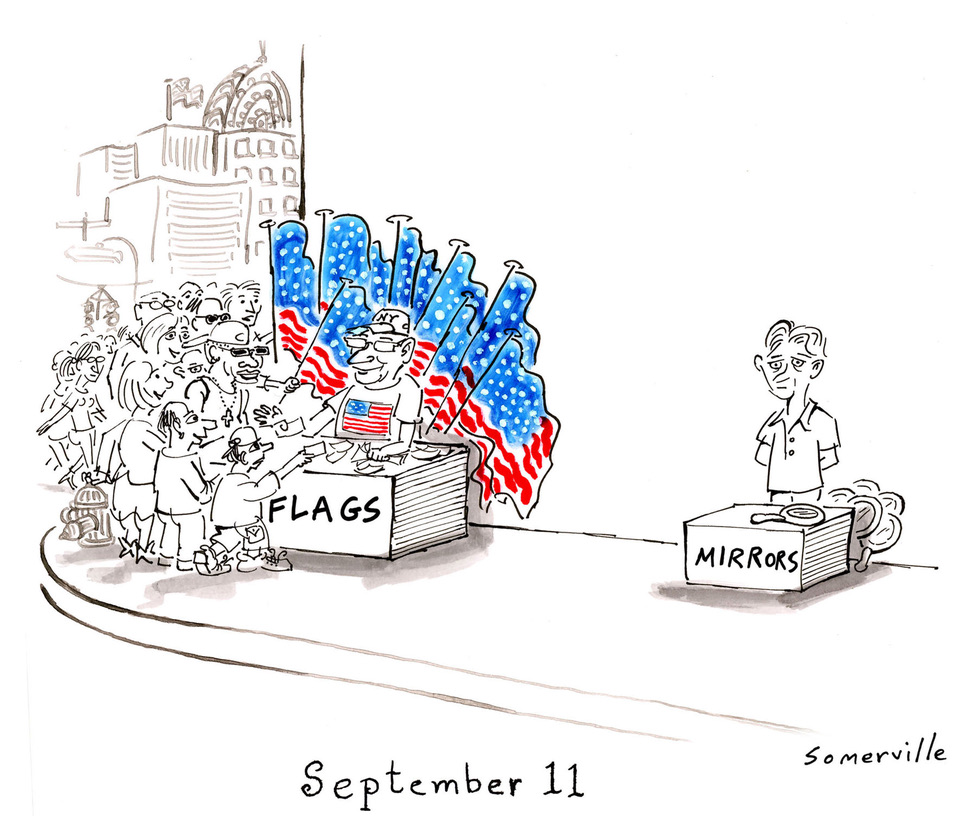

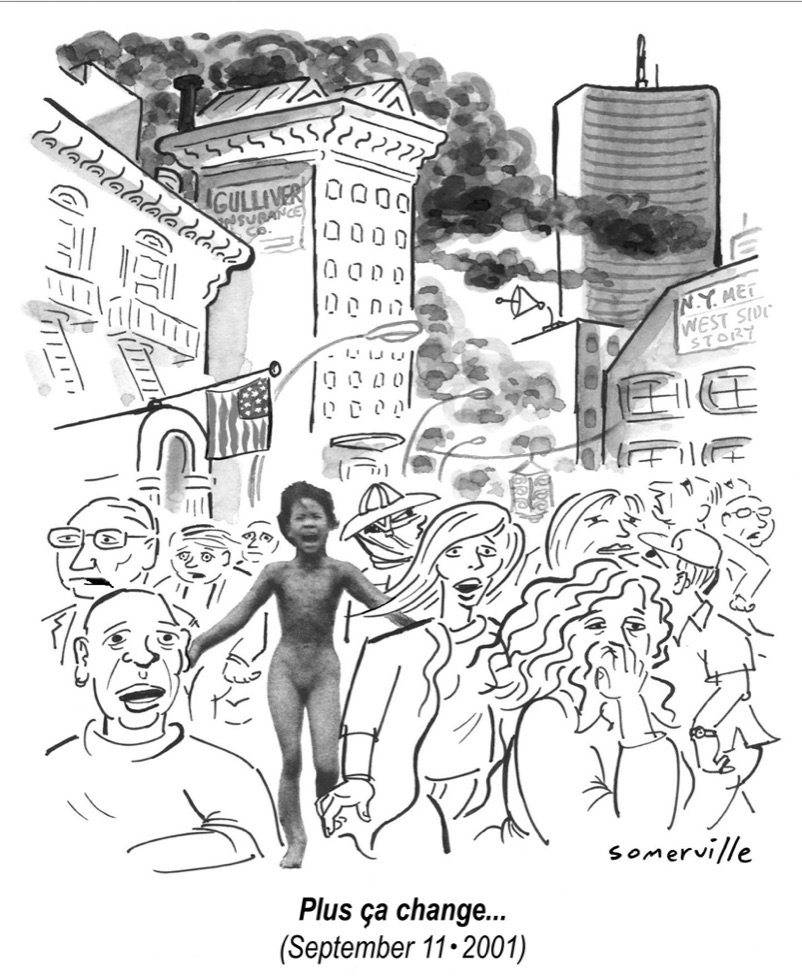

Phil’s other career highlight came from two different cartoons on the same subject matter, 9/11, produced one year apart. The first one he created 6 days after the event, eschewing all the clichés that were circulating. It was edgy and before its time, but it received enough positive attention to boost Phil’s career. The other cartoon a year later was apparently too edgy. The then editor of the Sydney Morning Herald declared: ‘Over my dead body will that ever see the light of ink.’

‘Flags and Mirrors’ – Phil’s cartoon published six days after the events of September 11, which resulted in a boost in his career

’September 11th First Anniversary – Phil’s cartoon one year after the events of September 11 that was refused publication but ended up on Media Watch.

This spiked response intrigued Phil and led him to conclude that there must have been something important about that cartoon. He took a few steps of curiosity towards Media Watch and before he could take a few steps back, David Marr (then host of the show), was on air showing the cartoon and declaring it suppression of media. “There was this huge reaction,” Phil says. “Hundreds and hundreds of letters sent in, some damning, some glowing, but probably 60% or 70% of it was positive, saying it should have been published.”

Three months later, Phil was sacked by attrition: the back page was redesigned, and he was ‘omitted’. “It’s still a highlight, because that’s what a highlight is, it’s antiseptic, agnostic. It doesn’t have to be positive.”

***

It seems to me that Phil’s career reflects his personal avoidance of black and white thinking, his personal hunt for the layers of grey in the world and in humanity. Schooling exposed him to some of the worst extremes of human behaviour. It would be understandable if he had leaned towards unbalanced rage after that. Yet, he seems more inclined to seek reasoning and understanding. “They were all bitter and frustrated people… just taking it out,” he says of the abusers he encountered at school.

Seeking understanding is a philosophy that informs his outlook on life as well as his practice. During our two hours of chatting, he would come back to this point, often using different visual metaphors to demonstrate: “Human beings are messy. It’s like a spilt bottle of honey, and it’s just hard to fathom, hard to clean up, it’s sticky – and so it’s better to kind of look into and see that every person has a motivation, and it comes from things you wouldn’t suspect. If you can do that then you don’t move into that sort of removed hatred. You know, someone pisses you off, but as soon as you get to know them you can’t be like that anymore. That’s well known to philosophers back to ancient Greece, but we haven’t learned that one yet. And our life, the global life, the global development is going away from that.”

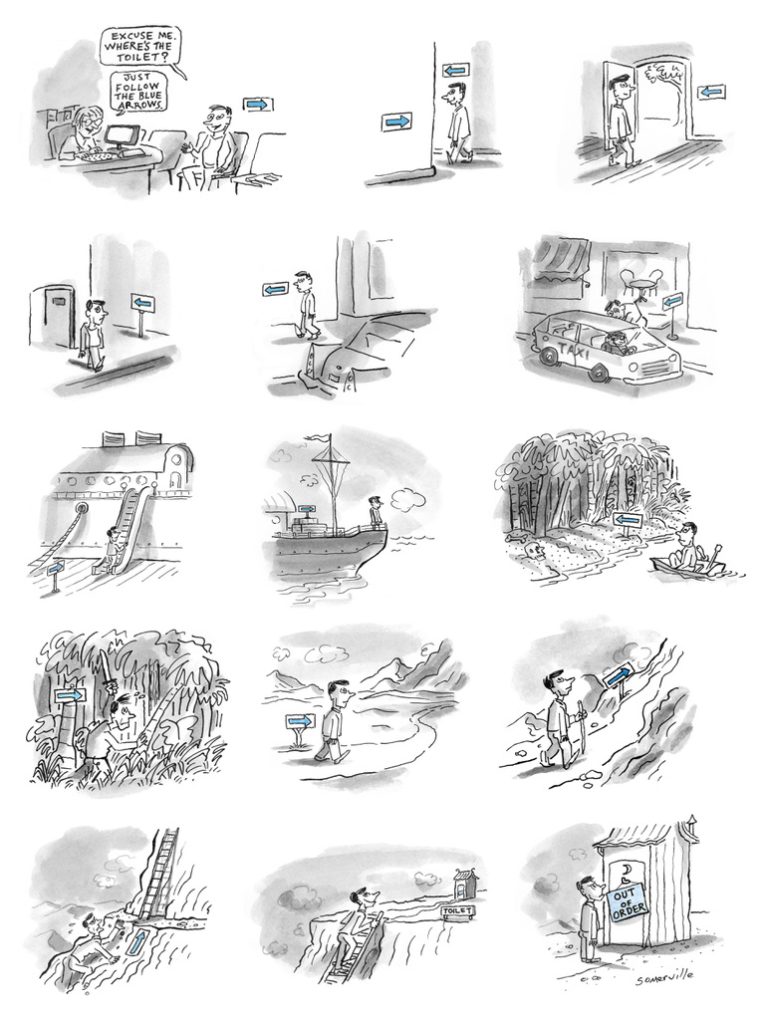

‘Toilet Odyssey’

By the end of our conversation, I can see that through his craft, Phil finds the kinks in hard lines and illuminates the lost ideas in the messy middle of dualistic thinking. Friend and peer Alan Moir once said of him: “I knew you were made to be a cartoonist because I see you have a chip on your shoulder. Now you have to get one on your other shoulder and you’ll draw with balance.”

When I get around to asking him if I can take some photos, the roof is cutting a hard-line shadow at his knees, making it hard to bring him into balanced exposure. The phone camera doesn’t cope with the extremes. It seems to get confused, like it wants to simplify the image by adjusting fully to compensate for one or the other – the dark or the light. The duelling light causes a moment of confusion, the irony of which is not lost on me.

In the end I have to cut off Phil’s knees as well as the harsh whites of full sun in order to capture him in some kind of balance. It’s appropriate that I later get a better shot of him in his drawing room, where he spends his time finding his own darks and lights, putting them together and ultimately finding the many layers of grey in between.

‘What’s Your Hopes and Dreams’

Phil continues to produce both political and non-political cartoons – “I don’t value one over the other. I think the positive of the non-political is that people don’t feel they have to care for that moment or about the girth and the weight of the world’s problems. It’s time out.” You can learn more and get in touch with Phil via his website: Phil Somerville – cartoonist (somervillecartoons.com). If you wish to receive fortnightly cartoons directly from him you can subscribe to Line of Thought by emailing an enquiry to: phil.somerville@somervillecartoons.com.

If this story has raised any issues for you, you can access support from the following services:

1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732 | 1800respect.org.au

Lifeline: 13 11 14 | Text 0477 13 11 14 | lifeline.org.au

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.