Rhiannon and Alasdair after a satisfying day of forest-growing.

Story and photographs by Belle Butler

Syntropic agroforestry around the world is demonstrating a promising solution for reducing the climate crisis. In a recent hands-on workshop in Hazelbrook, participants created a food forest and learnt how they could ‘bend time’ by accelerating its growth to help create a fertile earth for all organisms to survive.

On a crisp Hazelbrook morning a group of seven set out to grow a forest. The low sun was miserly in its distribution of warmth but after a few minutes of digging, jackets came off and hats went on. The team worked to a pleasant soundtrack: the rolling crunch of wheelbarrow on gravel, the rhythmic scratch of scooping shovels, the coming and going of rooster-crow, dog-bark and wind in the trees. They added their own banter to the mix.

Hard at work growing a forest

They were enthusiastic workers, keen to get their hands dirty after the previous week’s full-day lesson on the principles of syntropic farming and food forestry. The two-part workshop was run by Rhiannon Phillips of Mountains Gourmet and Alasdair Bednall of Entangled: Edible Ecosystems. “I really wanted to bring a new form (well, new to me anyway) of regenerative growing to the Blue Mountains, my home, and I knew Alasdair has a wealth of knowledge to share,” said Rhiannon about her decision to run the workshop. Alasdair added, “I believe that the workshop/installation model is the most compelling as it offers a group educational context that empowers participants with the theory and practical know-how to begin their own journey. It also allows the knowledge to permeate into a wider segment of the community.”

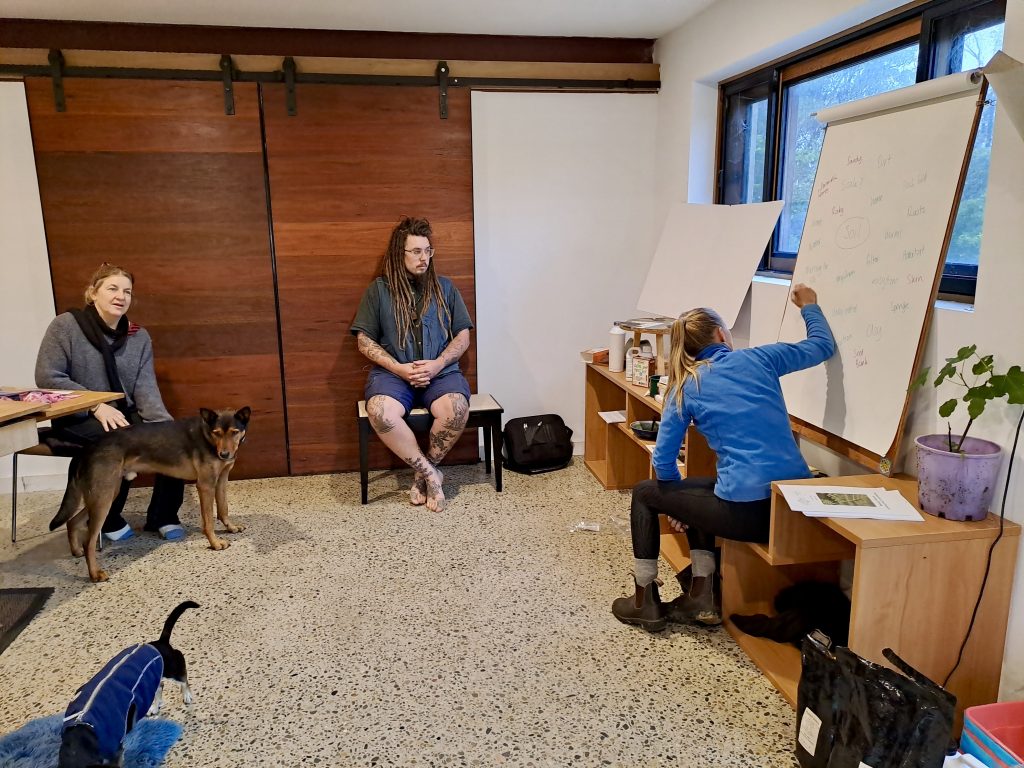

Day 1 in the ‘classroom’.

Rhiannon teaching about soil health.

The workshop included a day of knowledge-sharing followed by a day of forest-building at the home of Hazelbrook resident Vicky Critchley. A big fan of garden working-bees, Vicky was a welcoming host, pleased to offer her property as the site of the Food Forest project. While she will be required to tend to the forest over the coming months, a follow-up in spring will give all participants the chance to see the progress and take part in a second round of planting.

Growing a food forest in Hazelbrook. Participants talk about their experience of the workshop, their reasons for getting involved and what they hope to gain from it.

Why run a workshop on Syntropic Farming and Food Forestry?

Syntropic agroforestry is a regenerative food and resource production system that rehabilitates the land and builds biodiversity while providing yields. It relies on human intervention as a change agent to accelerate the process of forestation, as well as to ‘disturb’ natural processes in order to maintain higher yields and healthier systems.

“Workshops are important for knowledge transfer and succession,” said Rhiannon. “And teaching people how to grow their own food is empowering for all parties involved. Not only do people learn skills that their ancestors practiced for thousands of years and may have lost over time, but they also have the opportunity to regenerate the land that they’ve been granted custodianship of.”

Workshop participants taking a closer look at the site for the food forest

Rhiannon and Alasdair met a few years ago at a certified organic farm that Rhiannon was managing at the time. Previously she had completed an Honours degree in Animal and Veterinary Bioscience at the University of Sydney and worked in conventional agriculture, each of which solidified her perspective about what not to do.

Rhiannon was disappointed about the lack of interest in soil life throughout her degree and in practical application. She witnessed the swift degradation of land due to tilling practices and use of salt-based fertilisers and pesticides. “I was so shocked that none of the farmers were ever directed to assess their soil health by expert consultants. It was always just a prescription of more chemicals to ‘balance’ the constipated soils,” she said.

Rhiannon talking about the broad positive impact of regenerative food growing.

As she veered away from conventional farming, Rhiannon gained experience in organic practices. She participated in various courses, including recently completing her Permaculture Design Certificate at the Lithgow Transformation Hub and a Soils masterclass with Nicole Masters. In July 2022 she started her own food farming business, Mountains Gourmet. Mountains Gourmet uses private plots of land in Lawson and Bullaburra to grow food using organic farming methods and permaculture principles. Rhiannon sells the produce to local cooperatives and other local food distributors.

Rhiannon at her food growing patch in Lawson.

Healthy organic kale ‘trees’ at a Mountains Gourmet plot in Lawson.

“I am passionate about getting as many people to feed themselves as possible,” she said, “as well as helping people achieve things through educating and looking after the environment.” Mountains Gourmet runs food-growing workshops in order to realise this passion.

Alasdair came to the same conclusions as Rhiannon about conventional food growing, but his deep dive into agroforestry was more personal. “It started with a general sense of despondence towards modern society that I sensed was reflected in the growing suffering of both humans and the earth,” he said. “In a period of self regeneration I turned to local old growth forests in England where I was deeply moved by the prosperity and ebullience of life.”

After gaining knowledge via forest growing YouTube clips, and later permaculture and other regenerative agriculture courses, Alasdair felt that he could grow forests that would be similarly healing for others. “Regenerative agriculture is not just about regeneration of the land itself, but also the regeneration of us and our connection with the land,” he said.

Alasdair’s food forest at his home (supplied)

Alasdair at the site of the Hazelbrook workshop

What are the objectives of syntropic agroforestry?

Bees and butterflies pollinate. Worms maintain soil health. Scavenger animals tidy up. What do humans do? Questioning the human ecological function is akin to asking what the meaning of life is. It gets messy. But in agroforestry this is an essential question, pondered by workshop participants and hosts alike.

It was established during the workshop that one important ecological function of a human is to incite change. We are ‘disturbance agents’ with the capacity to shake things up for better, or for worse. Think: using fire, planting and removing trees, or simply pruning a tree. We can steer natural processes in certain directions.

Workshop participants on the site of the food forest

Unfortunately, much of our power-wielding has steered ecosystems towards decline. Globally, nearly a quarter of the earth’s land is degrading. This results in expanding deserts, reducing capacity for food production and drying up of water sources. Increased surface area of deserts and drylands feeds back into the loop, creating a hotter climate that in turn perpetuates the problem.

Alasdair refers to this as a “threshold moment in humanity.” He explains: “We have difficult decisions to make about the future we envision as a collective. I strongly believe that immersion in forest ecology offers an invitation back into human communion with the earth and an understanding that our vitality is based on cultivating the web of all life; creating a fertile earth for all organisms to thrive.”

Alasdair explains the process of natural forest growth

With conventional agriculture being a major factor in the desertification of once fertile land, syntropic agroforestry offers a positive alternative. “Forests provide beauty to our living spaces, securing water tables and making for more liveable suburbia,” said Alasdair. “They also become a catalyst for increased biodiversity, abundance of life and a host of resources necessary to sustain humanity beyond simply food. It is a dynamic solution to many of the pressures that have been created from our insatiable globalisation.”

Left alone, a forest may take hundreds of years to reach maximum biodiversity, but syntropic agroforestry can accelerate this process. “Humans are uniquely placed to bend time in the forest narrative,” said Alasdair. Based on this system, humans plant vegetation in a way that mimics the structure and ecology of natural forests. However, with the intention of cultivation, trees are selected for their wide range of benefits including food, resource or medicine, as well as their unique ecological niche. They are planted with intentional positioning and sequencing to optimise their role in the system.

Alasdair explains the role of each plant

Agroforestry is not new. It combines existing practices used for thousands of years. Examples of Indigenous agroforestry discussed at the workshop include: Creole gardens in the Caribbean that combine productive trees with small livestock; Zai farming of Sub-Saharan Africa in which holes are filled with deep layers of manure for cultivating grasses and annuals; the banana circle technique of Baganda Peoples in Uganda where bananas are planted in a circle with a compost pit in the middle; and Vietnamese Taungya Systems in which farmers plant trees among crops in order to provide shade and improve soil fertility.

Relearning and adopting these practices on a broader scale has the potential to regenerate degraded land around the world and reduce encroachment of agricultural practices into existing biodiverse regions. “All of the resources required for maintaining a healthy forest are obtained from within the forest itself. There are no inputs, no increasing costs,” said Alasdair. “They work within the framework of a continuous self-propelled upward spiral of prosperity, rather than a system that requires inputs in one end and that generates pollution at the other.” As a method of regenerative food production that also sequesters significantly more carbon than industrial methods, it is a promising solution for helping to combat the climate crisis.

Jackson pondering plants

Vicky scoping out the layout of the food forest

“Learning how to grow produce syntropically, whether it be a large area or tiny kitchen garden, is simply a step in the right direction to working with nature rather than against it,” said Rhiannon. “I feel it’s important for people to begin to understand nature better so we can all move together into a more sustainable future.”

Key to achieving the desired outcomes is creating and maintaining forests that continually feed the soil providing balanced systems for hungry plants to thrive. It’s a bit like a circular economy of nutrients, that maintains biodiversity and creates zero waste.

“Soil is not just dirt,” said Rhiannon. “It’s literally holding up our civilisation.” During the workshop she discussed a number of factors that influence soil health, giving practical tips for use at home. One take-home message that a few participants cited as particularly useful was to regard weeds as indicators. They come in to serve a function. Particular weeds serve particular functions. Observing which weeds are growing where can provide information about what the soil needs to be healthy.

Manure is a very important ingredient for soil health

Making sure to cover the soil quickly in order to protect microorganisms

Putting agroforestry into practice

The first step participants took at the working bee was to scope out the layout for Vicky’s food forest. This resulted in two snaking lines running East-West to efficiently manage the edge habitat, make the most of the northern sun and allow easy access for maintenance. Next on the agenda was the crucial task of tending to the soil. Participants warmed themselves by digging deep holes in which generous helpings of horse manure and compost were thrown.

Perks of a working bee

Banana plants went in, spaced roughly 3 metres apart. Alasdair explained that the use of banana plants was to allow for their nutrient rich biomass to support the system: “Bananas are one of the primary early succession plants for building prosperous life in the soil micro biome.” Although in this case they were not being used primarily for their food crop, a bunch of bananas might be a happy bonus for Vicky in the future.

Breaking up roots to make deep holes

Planting was a welcome relief after digging

After the banana plants, pioneer species – plants that are typically the first to colonise a newly disturbed environment and help to make the soil more hospitable to other plants – like eucalyptus, acacia, Virgillia, elder, perennial grasses and nutrient miners went in and were positioned with consideration of their particular ecological niche. This was followed by thick layers of mulch and finally a spread of chickpeas as nitrogen fixers and oats for their fast growing biomass to then ‘chop and drop’ and add nutrients into the soil.

Splitting bana grass

Vicky happy with the result

At last the sun was low again, this time on the other side of the horizon. It cast long shadows across the fresh greens of the young forest and set a sparkle to participants’ sweaty brows. The air was filled with satisfaction and the pungent smell of mulch. “Imagine if we had ten people doing this in their neighbourhood,” said Rhiannon. “On their own land, sequestering carbon and positively impacting all that soil… The power of that is huge.”

If you wish to take part in any future workshops with Rhiannon and Alasdair they’d love to hear from you:

Alasdair on Instagram: @the_wondering_river

Alasdair’s email address: Alasdair.bednall@gmail.com

Coming up:

GROW AT HOME WORKSHOPS — Mountains Gourmet

This workshop will focus on winter gardening, heating small greenhouses using compost and poultry AND creating hot compost ready for Spring!

Details:

Date: 17/06/2023

Time: 9.00-1.00pm

Location: Bullaburra

Price: $140

Places left: 7

BYO snacks, gloves, water.

Take home seedlings and produce.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.